School civics classes teach that the Constitution guarantees the right to remain silent, freedom of speech, equal protection under the law, and a wall of separation between church and state.

Except the founding document never actually talks about a wall.

“It’s something that the courts and anti-religious groups created to keep religion out of our public square,” says John Bursch, senior counsel at Alliance Defending Freedom.

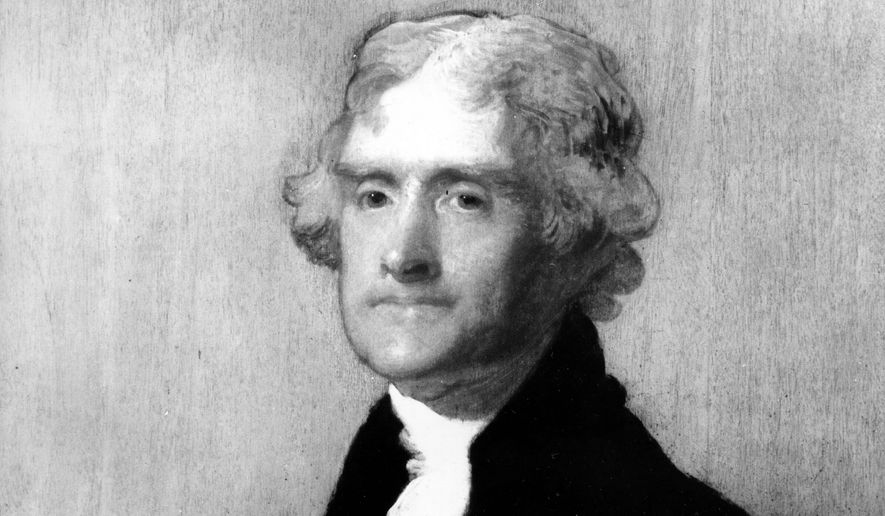

Like so much of founding-era wisdom, the concept of separation of church and state sprung from the mind of Thomas Jefferson — though he was not part of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, nor was he in that first Congress that drew up the amendments that would become the Bill of Rights.

The third of those 12 amendments sent by Congress to the states for ratification included the admonition that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Only 10 of the 12 amendments were ratified at the time — the first two didn’t earn enough states’ approval — which is how the third amendment became the First Amendment in late 1791.

Enter Jefferson a decade later, in early 1802, now in the White House and being battered by his political enemies, the Federalists. Publicly pious and eager to show it, they promoted days of fasting and prayer and wanted Jefferson to follow John Adams’ lead and proclaim them from the newly opened White House.

He fired off a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut, in which he laid out his vision of “a wall of separation between church and state.”

The Library of Congress in the 1990s decided to try to figure out more about what was behind Jefferson’s letter.

They roped the FBI into helping out, and the bureau used its state-of-the-art lab facilities to recover the rest of Jefferson’s original draft.

The draft reveals that Jefferson originally wrote of a “wall of eternal separation between church and state.” And the draft also reveals that Jefferson had no intention of it being “a statement of fundamental principles; it was meant to be a political manifesto, nothing more,” James Hutson wrote for the Library of Congress.Read the rest of the story HERE.

If you like what you see, please "Like" us on Facebook either here or here. Please follow us on Twitter here.

No comments:

Post a Comment