More Money, Worse Results

I keep an old black-and-white photo on my bedroom wall. It was 1956. I lived in New York City and was in third grade. The picture shows 43 students, one teacher, and no aide. My school had a principal, no assistant principal, no counselors, and no deans. We all learned. Students became doctors, lawyers, accountants, and writers. The inflation-adjusted per-pupil spending at the time was about $3,600.But we live in very different times now.

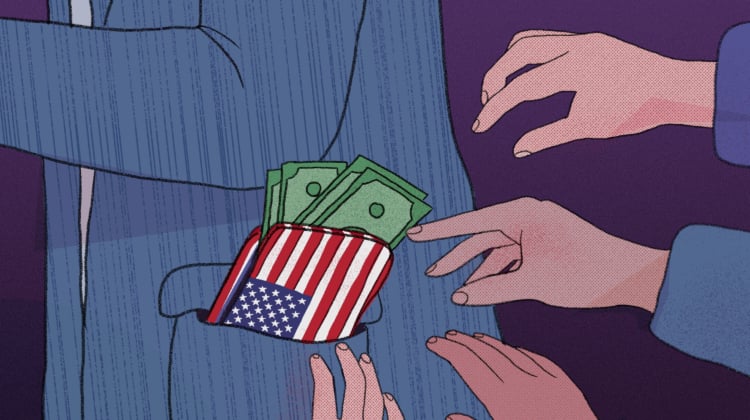

A new paper by the Reason Foundation reports that, nationally, K-12 public schools received $946.5 billion in local, state, and federal funding in 2023. After adjusting for inflation, the average annual per-student cost increased by 35.8% between 2002 and 2023. K-12 education spending on employee benefits—including teacher pensions, health insurance, and other expenses—increased by 81% over the same period.

New York had the highest per-student budget at $36,976, more than ten times what it was when I was in third grade in 1956.

California, my adopted home, is among the highest spenders. According to the study, the state now spends $25,941 per student, placing it among the top eight nationally. The sharpest growth has occurred in the past few years.

Since the COVID pandemic, California’s per-student spending has surged by 31.5%, up from $19,724 in 2020 to its current level.

Much of the nation’s school funding goes to increased staffing. Data released in December by the National Center for Education Statistics show that public schools added 118,000 employees in 2024 despite serving 135,000 fewer students.

Looking at a longer timeline, student enrollment has declined by 1.4 million (a 2.8% decrease), while employment has increased by 479,000 (a 7.3% gain) since 2018-19.

Interestingly, most employment gains are not primarily driven by an increase in classroom teachers. From 2018-19 to 2024-25, schools added 389,000 non-teaching jobs.

Administrative bloat in public schools is hardly new. Benjamin Scafidi, an Economics of Education professor at Kennesaw State University, found that the number of non-teaching staff at U.S. schools increased by 702% from 1950 to 2009, while the number of teachers increased by 252%. During this period, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores fell.

Scafidi wrote that this “irresponsible use of taxpayer dollars is indefensible,” and that was before the salary surge. From 2010 to 2022, administrative staff grew by another 41%, while overall school employment increased by only 10%.

Is all this spending helping students at all?

A recent report from the Brookings Institution says absolutely not. Economist Sarah Reber and fellow Gabriela Goodman examined the latest available data before the steep declines in student achievement since the COVID school closures. They find that “substantial increases in per-pupil spending over time have often been met with stagnant academic achievement.”

Additionally, economically disadvantaged students in higher-spending states “don’t achieve better outcomes compared to their counterparts in lower-spending states.”

In California, the return on investment is especially poor. The 2024 NAEP scores show that only 28% of California’s 8th-graders are proficient in reading.

One better use of education funding would be to pay good teachers more. --->READ MORE HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment