|

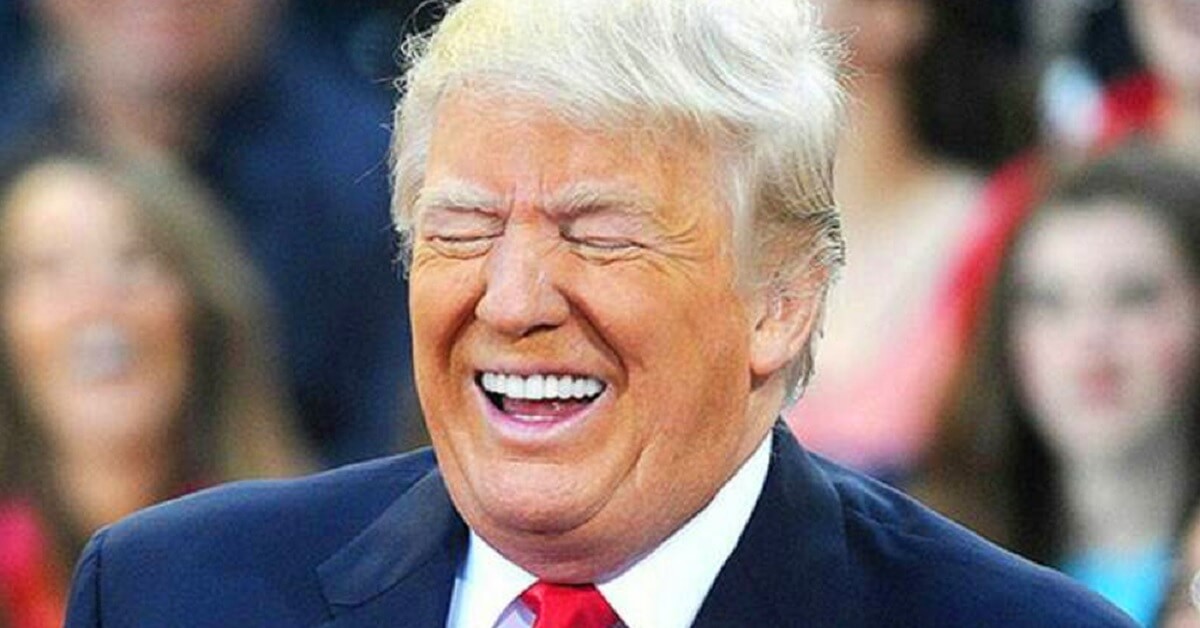

| Jason Reed/Reuters |

Probably not, but some Democrats are trying.

In the torrid final weeks of the long presidential campaign, the unique confluence of legal, procedural, and constitutional initiatives to alter the electoral process has been publicly glimpsed only occasionally. These are all activities undertaken by Democrats and Democratic state legislatures, presumably motivated by the uniform horror with which they endured Donald Trump’s election as president. Though his promise to “drain the swamp” was intended to apply to offenders of both parties steeped in the complacency and bad habits of the governing political class, the Democrats naturally consider that they were the principal target of Trump’s crusade. The substantial number of Republicans whom he was excoriating with the same rugged vocabulary as the Democrats were generally Never Trumpers who sped into informal alliance with the Democrats.

Most of the old Bush-McCain-Romney Republicans, including the late John McCain and Mitt Romney himself; former secretary of state, chairman of the joint chiefs, and national-security adviser General Colin Powell; the third-place contender for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination race, former Ohio governor John Kasich; and a large number of other prominent former Republican officeholders are in this camp. At one level they may be taken as a bipartisan consensus in favor of legitimate reform, as has periodically arisen and effected orderly modifications to the Constitution for two centuries. It is also possible to construe this spontaneous enthusiasm for changes to the electoral system as a self-serving effort by the locked-arms bipartisan Washington political class to raise the drawbridge, pull down the blinds, and repel boarders, especially those who come snorting into Washington pawing the ground in anger at the evils of their long incumbency.

The easiest and most plausible focal point for their activity is that permanent butt of discontent, the Electoral College. All but the smallest states send a number of pledged electors to choose the president that is equivalent to their share of the country’s population. The number of electors from each state is identical to the delegation it sends to both houses of Congress, and as each state has two senators, that does give the smaller states a slight leg up, but is not relevant to the comparative weighting of the larger states, especially the approximately 25 states that have from nearly ten electoral votes to the largest delegations, California (53) and Texas (38), of the total of 538. Complaints against the system normally arise after the winning candidate has received a smaller popular vote than the nominee of the other main party. This occurred in the 2016 election, when Hillary Clinton led Donald Trump by 2.9 million votes but lost in the Electoral College, 304–227. She won large pluralities in California, New York, and Illinois but lost Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin by total of only 80,000 votes. (It has been little noted that even if 40,000 of those votes had been cast for her and she had won those states by a hair, if just 16,000 Clinton votes in New Hampshire and Nevada had gone to Trump, he would have won anyway, albeit by just two electoral votes — this sword cuts both ways.)Read the rest from Conrad Black HERE.

If you like what you see, please "Like" us on Facebook either here or here. Please follow us on Twitter here.

No comments:

Post a Comment