|

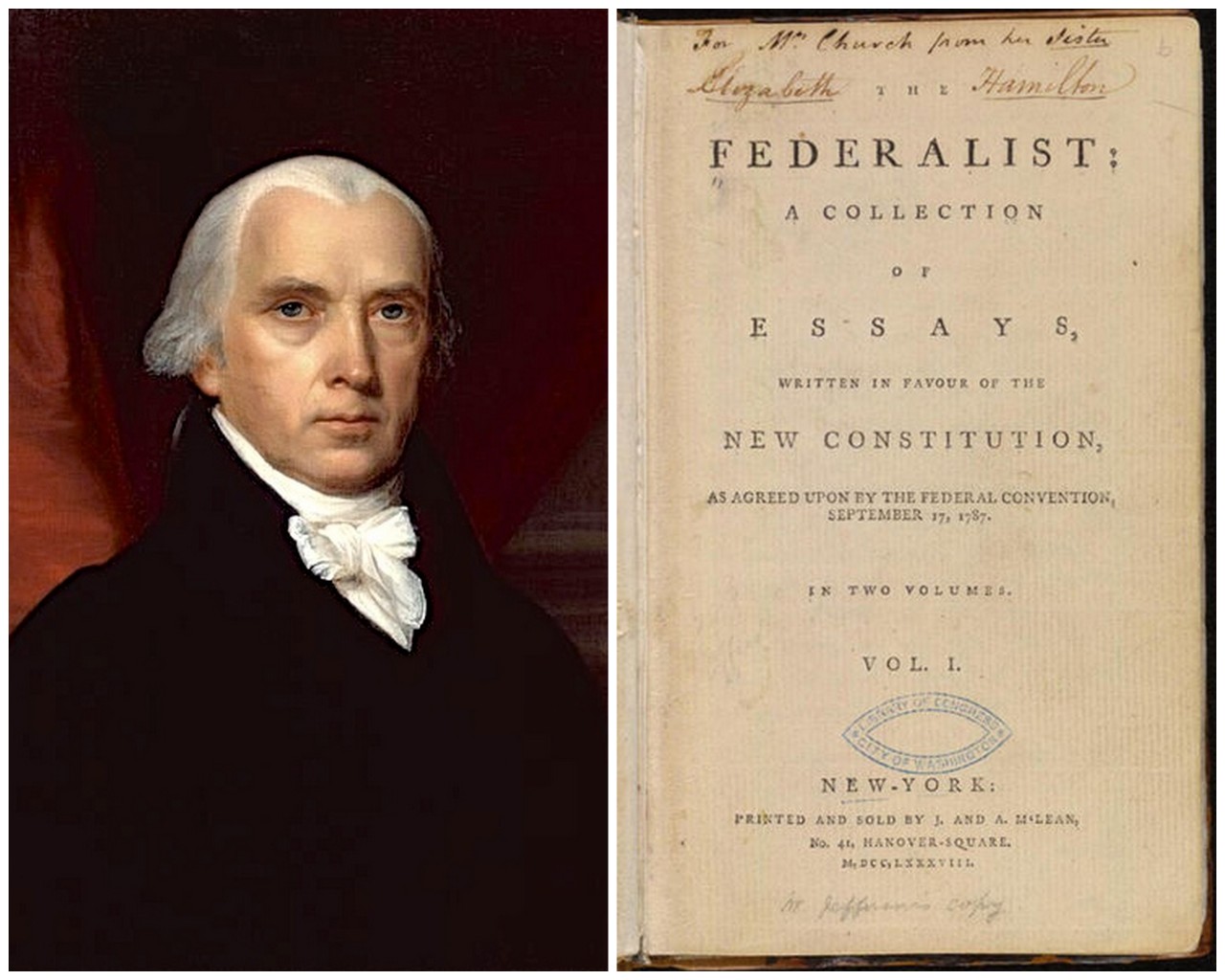

| CHBD/Getty Images |

In the 1780s, our Founders feared many things about the tenuous future of the republic they were creating, but a tyrannical judiciary that acts as supreme to the other branches wasn’t one of them. They would have laughed at the spectacle of two parties at each other’s throats not over the balance of power in the Senate, but over how that balance of power will determine the tilt of the Supreme Court, where the true power resides these days.

Regardless of whom Trump nominates to fill the latest Supreme Court vacancy, both sides will vociferously question the nominee over his or her views of certain court precedents. But we could go a long way toward cooling some of this political acrimony (and fixing our republic to boot) if we focused on just one court precedent: The Supreme Court’s own declaration, during the Warren era, that its decisions over the Constitution are exclusive, final, and universally binding over the other branches of government. It’s this legal fiction that is fueling the high-stakes fights over every other precedent. If we all agreed to end judicial supremacy, control over the other two branches of government – with their more robust powers to affect their respective interpretations of the Constitution – would matter much more than control over the Supreme Court.

Judicial supremacy is an absurd and tyrannical fiction

In a 2017 report, the Congressional Research Service observed that “early history of the United States is replete with examples of all three branches of the federal government playing a role in constitutional interpretation.” Members of Congress weren’t so complacent in their duties and, as the CRS observed, never sat idly allowing the courts to wield “a final or even exclusive role in defining the basic powers and limits of the federal government.” They subscribed to Madison’s view in Federalist #49 that “the several departments being perfectly co-ordinate by the terms of their common commission, neither of them, it is evident, can pretend to an exclusive or superior right of settling the boundaries between their respective powers.” He emphatically believed that “each [department] must in the exercise of its functions be guided by the text of the Constitution according to its own interpretation of it.”

It wasn’t until Cooper v. Aaron (1958), during a time when the high court was reinterpreting the Constitution beyond recognition, that it brazenly declared “the basic principle that the federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law of the Constitution” as “a permanent and indispensable feature of our constitutional system.”

While the case itself dealt with desegregation of schools in Arkansas, an outcome we all support, the court grabbed power for itself by noting that the court doesn’t only bind the parties in an individual case but prevents states from doing anything to “indirectly” undermine the outcome and precedent of the case “through evasive schemes.” In other words, the judiciary is really a legislature and passes “laws” with majority opinions that are self-executing and universally binding even on non-parties and the other branches of government. As the court wrote emphatically at the end of the opinion in sly and gratuitous dictum, “The interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment enunciated by this Court in the Brown case is the supreme law of the land.”

Thus was born the notion that the court can declare abortion, gay marriage, early voting, voting without photo ID, and affirmative action a part of the Fourteenth Amendment and have it be regarded by the body politic as “the law of the land.” --->Read the rest from Daniel Horowitz HERE.

If you like what you see, please "Like" us on Facebook either here or here. Please follow us on Twitter here.

No comments:

Post a Comment